World trade is possible because of the international shipping industry. Thousands of merchant vessels travel around the world through the seas, on international routes connecting ports distant from each other. Some of the busiest routes have been suffering, for many years, a threat to the security of ships, cargoes and crews, piracy.

This threat has been along maritime activity since ancient times, for instance, the first record in history of the organization of a naval campaign against pirates, dates back from 1350 BC and belongs to the Minoan civilization. Moreover, Julius Caesar, the Roman emperor, was a victim of pirates on the Aegean Sea, and as a result, all the pirates were crucified (Dalaklis, 2015).

Along time, pirates had exercised their business as despicable thieves, war instruments, or as civilizations in their right. States had employed three strategies, through history, to deal with pirates: collaborate, tolerate or suppress. From the old pirates of history to the modern times pirates of the Malacca Straits, Somali and West African, their operation has always been in either complicity with, or in the absence of, authorities of the State.

As stated above, piracy operates mainly in the Strait of Malacca, Somalia, and the Gulf of Guinea. Pirates, over these three regions, utilize very different models of piracy: Somalia is hijacking and ransom operations in the absence of an authority of the State, in the Strait of Malacca piracy is focused in theft and robbery at sea, and in the Gulf of Guinea the primary activity is the steal of oil, but increasing today the abduction of crew for ransom. The piracy in the Asian region and the Gulf of Guinea occurs mainly on territorial waters (Wajle, n.d.).

While a global response was taking place to attack piracy off the coast of Somalia, in the Gulf of Guinea, alarms were calling about the expanding insecurity in that area. Nowadays, the Gulf of Guinea arises like the riskiest and dangerous areas, considering the percentage of successful pirate attacks and the violence. In fact, in 2012, the United Nations (UN) deployed a special team into the area to evaluate the worrying situation (Kamal-Deen, 2015).

The report from the UN was a call to the international community and regional states to respond to piracy; as a result, in 2013 in Yaoundé, Cameroon, the Code of Conduct Concerning the Repression of Piracy, Armed Robbery Against Ships, and Illicit Maritime Activity in West and Central Africa was adopted by the States of the Gulf of Guinea, with extensive international support.

Even though the adoption of the code, the first hijacked ship occurs a few months later and also pirates attacks increase its rate in the Gulf of Guinea at the end of 2013; furthermore, until today others ships were successfully hijacked, reinforcing the necessity of effective counter-piracy measures. In a pragmatic view, the success of the international and regional response depends on three factors: the awareness of the parties involved, knowledge of the operational environment, and the most essential, the full understanding of the evolution of the situation (Kamal-Deen, 2015).

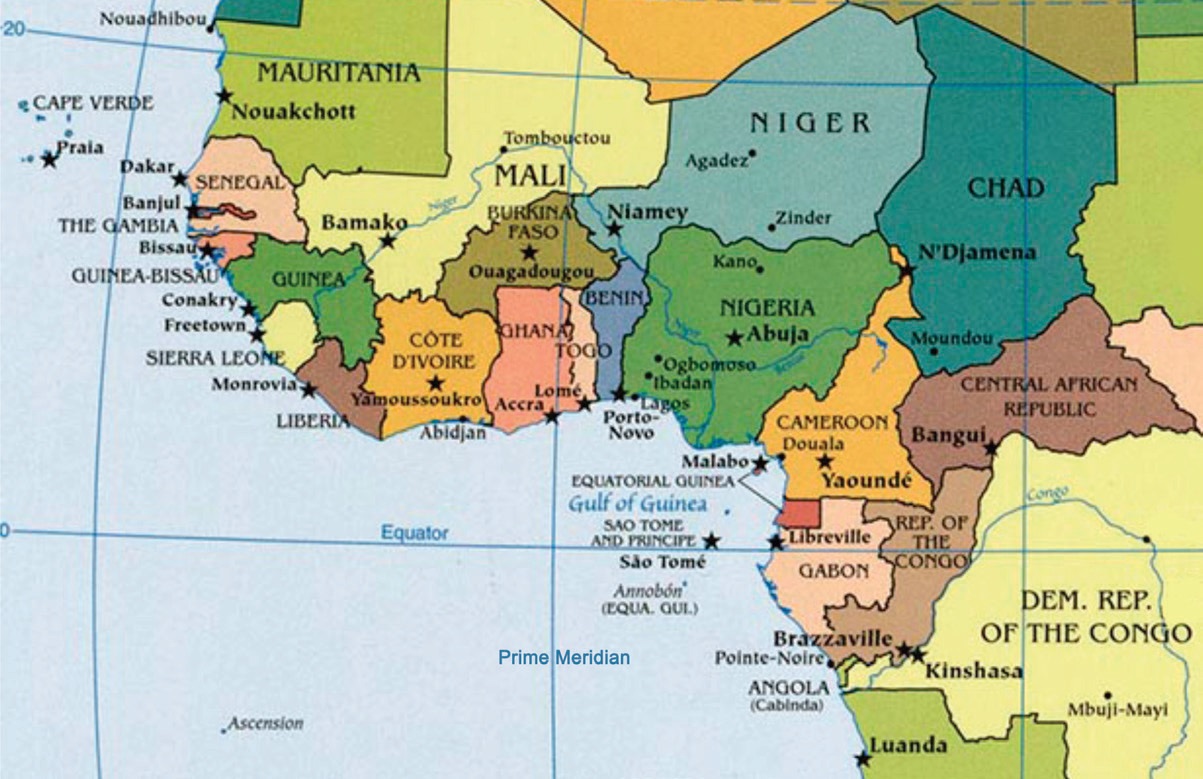

The Gulf of Guinea offers 5,000 nautical miles of coastline for the maritime industry. The conditions in the Gulf seem to be ideal for the business of shipping due to a large number of natural harbors, the inexistence of chokepoints and the scarcity of adverse weather conditions. Moreover, it is possible to find large amounts of hydrocarbons, fish, and others natural resources. These particular characteristics and conditions offer a unique potential to the maritime commerce and development. The broader Gulf of Guinea from Cape Verde to Angola (Figure 1) is considered the main hub of transit and facilitates the fast economic growth of the region, with an average of 7 percent since 2012. However, there is a threat to this economic boom, piracy. Piracy attacks have been increased in the Gulf of Guinea; furthermore, from 2012 the rate of attacks in the region has overcome the Gulf of Aden as the area with the main number of reported attacks in the world; also, the attacks tend to be more violent (Osinowo, 2015).

Due to a limited presence of maritime security off the coast of West Africa, the theft of oil is a n Figure 1. Gulf of Guinea Maritime Region. Mauricio Elgueta Orellana: Piracy in The Gulf of Guinea plague and the main illegal activity in the Gulf of Guinea, for example in 2013, Nigeria daily lost were between 40,000 and 100,000 barrels of oil because of the theft and the illegal bunkering (Council, 2014), and during 2017 that amount was increase to 400.000 barrels of oil per day, giving to the countries of the region an estimated loss of US$1.5 billion per month (This Day, 2018) .

The governments in the area have been slow to comprehend that their absence in the maritime space is a factor that not only diminishes their incomes, it also threatens security on land, due to illegal activities at sea has their beginning and end on shore. The threats affecting the Gulf of Guinea represent a challenge and require the intervention not only of all the regional stakeholders but also internationally. Not many years ago the weakness of maritime security policies in the region and the absence of cooperation between countries were the main reason for the rise of criminal networks and, in addition, allowed them the diversification of their piracy activities.

One of the first initiatives in 2013 in the region was the adoption of, the Yaoundé Code of Conduct Concerning the Prevention and Repression of Piracy, Armed Robbery, and Illegal Maritimes Activities in West and Central Africa, created by the Economic Community Of West African States (ECOWAS), Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS), and the Gulf of Guinea Commission (GGC). The signatories governments are Angola, Benin, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Cape Verde, The Central African Republic, Chad, Congo, Cote d’Ivoire, The Democratic Republic of Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Sao Tome and Principe, Senegal, Sierra Leone, and Togo.

The code contains a clear and common policy against piracy and other illegal activities in the Gulf of Guinea; moreover, sets the measures to be taken against crime at national level, including the development of every State of a national maritime security policy, the creation of a national committee on maritime security for the coordination of activities, the creation of national security plans, and the prosecution of pirates among other offenders, in domestic courts (Code of, 2013). This initiative puts emphasis on the sharing of information, coordination and engagement of the States to declare their Economic Exclusive Zone (EEZ) and enforce their national laws.

At the international level, in 2014, the Council of the European Union (EU) developed the EU Strategy on the Gulf of Guinea. The strategy analyses the general scale of threats and risks posed to the States of the region and the EU. It also determines the possible actions to be taken by the EU, in support of the regional measures or procedures and with international collaboration, to help coastal States and organisations of the region to deal with the problem (Council, 2014). Furthermore in 2015, this Council adopts the Gulf of Guinea Action Plan 2015-2020, that outlines the support of the European Union member States to the region and its coastal states efforts to address the high number of challenges of both maritime security and organized crime (Council, 2015).

During 2017, 45 attacks were reported in the region, non of them outside of the EEZ of Nigeria. In previous years the crew succesfully avoided abductioon by locking themselves into the ship’s citadels, but in 2017, the pirates heavily armed, abducte 69 crew in 14 incidents. In the Niger Delta, Masters and Chief Engineers are the most valuables target for kidnaping and ransom. In numbers, 44 ships were attacked in 2017, an equal of 19% less than the previous year, but however the overall reduction, more crew were kidnapped due to in single raids more people have been taken (Dryad Maritime, 2018).

The reduction in the overall number of pirate attacks and hijackings represents an indicator that the implementation of policies has had an effect on the illegal activities in the Gulf of Guinea. Nevertheless, pirates have been moving their operations away of the scope of the territorial waters security protection, reaching the EEZ and international waters where the protective measures are less available. Hence, new consideration must be added to the current policy in order to enlarge the scope of it.

Many other responses to piracy, at international, national and regional level have been developed and include (Council, 2014):

– 2 UN Security Council resolutions about Piracy and Armed Robbery in the Gulf of Guinea, proposed by Benin and Togo.

– ECOWAS and ECCAS (regional organisations) have adopted several policies and initiated specific actions on maritime security, 2014.

– The Africa Union has adopted the African Integrated Maritime Security Strategy, 2014.

– IMO has begun a programme of table top exercises to promote among coastal states the development of national maritime security committees.

– Nigeria and Benin have initiated an increase in their resources and developed strategies in partnership and joint patrols.

– The EU Member States have incremented their support in the region by implementing regional and bilateral programmes.

– The EU has continued its support for the socio-economic development in the Gulf of Guinea, and it “Critical Maritime Routes” (CRIMGO) programme is reinforcing international and regional initiatives against armed robbery and piracy.

– United States, China, South Africa, Brazil and India have established bilateral programmes aimed at the policy formulation and coordination.

– The G8++ Friends of the Gulf of Guinea (G8++FOGG) (EU as a member) has established a better coordination, between international partners in GoG, on the maritime capacity building efforts.

Frustration perhaps is the word that better defines the situation of the legal aspects of the majority of the coastal States in the Gulf of Guinea. The lack of effective prosecution of pirates is extensive to many countries of Central and West Africa. This is a result of the absence of domestic laws for the prosecution of piracy and the weakness in the penalties applied and judicial processes. In several coastal states, navies and coast guards suffer a lack of prosecution powers, relying on the police and other governmental agencies for that imperative component of the cycle of enforcement. For example, in the conflictive area of Niger Delta, the trial for piracy and oil theft suspects could be extended for many months due to the reduced availability of judicial officers, giving the chance to many suspects to recover their freedom in a short period of time after the arrest (Osinowo, 2015).

One of the purposes of the Code of Conduct Concerning the Prevention and Repression of Piracy, Armed Robbery, and Illegal Maritimes Activities in West and Central Africa is the strengthening of domestic laws against piracy. The situation described above jeopardize the legal scope of the initiatives like the Code and many others, diminishing the efforts made by navies and coast guards in the fight against piracy, and at the same time, affects the achievements of compliant countries.

Even though international legislation allows countries to act beyond territorial waters, operational aspects affect the enforcement of these legal bodies. United Nations Convention of the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) on its articles 101 to 103 and 105 to 107, gives to the countries the faculties to operate on international waters (universal jurisdiction); unfortunately the means of many countries are not sufficient to achieve positive results in areas beyond national jurisdiction. Another aspect that contributes to this problem i

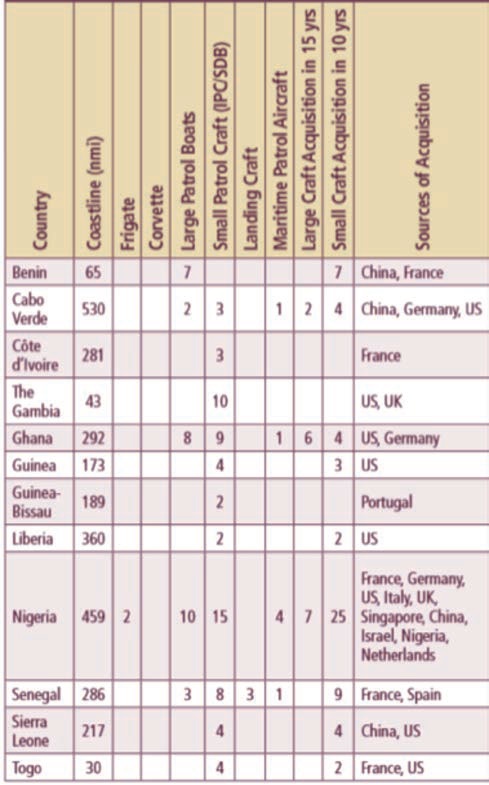

Table 1. Platform Profile of West African Navies and Coast Guards.

s the improper enforcement of the international law as the base of the national law.

An outstanding initiative in response to the challenges of armed robbery and piracy is the International Information Sharing Centers that divides the region into responsibility and operation areas, some currently in operation and others just planned.

The operational capacities vary from one country to another in the Gulf of Guinea; however, the joint work in the region will depend on the establishment of a strong position on three key actions: surveillance, response, and enforcement (Osinowo, 2015).

– Surveillance: Five countries have increased their coastal surveillance capabilities, Benin, Liberia, Ghana, Senegal and Nigeria, with international assistance from the United States and the EU. The main problems are the detection of vessels without Automatic Identification System (AIS) beyond the 40- 50 miles of the radar range, and in other countries the access to good broadband and maintenance capacity is an obstacle to the facilitation of communications and patrols.

– Response: The limited capabilities in Central and West Africa (Tab. 1) does not allow a continuous patrol in the order of one vessel every 250 nautical miles, even with all the means deployed in the area. Old ships (more than 25 years old) with different equipment and different suppliers, add new challenges of interoperability.

– Enforcement: As stated before, the lack of effective prosecution, the absence of domestic laws against piracy and the weakness of penalties and proper judicial processes, diminishes the effectivity of national, regional, and international efforts and initiatives in the region.

Thanks to the shipping industry it is possible the trade of goods in the world. Thousands of vessels navigate sea routes connecting many different ports, but the threat of piracy is latent in the busiest sea lanes.

Almost with the creation of the sea trade, piracy has been there along times on a side of shipping, which has constituted a challenge for entire civilizations, empires and countries to fight this threat. States have collaborated, tolerated or suppressed piracy, and its operation has been in complicity or in the absence of the authorities.

The Gulf of Guinea has arises like the most dangerous area in the world in terms of successful pirate attacks, taking the international attention to analyze and tackle this menace, in addition to the national and regional efforts to fight it.

Many national, regional, and international initiatives has been set up, which have instituted policies, legal and operational capacities in order to achieve an adequate response to piracy, however, not all of the coastal states in the Gulf of Guinea have the same dispositions and means to establish and enforce the legal and operational requirements against piracy.

The challenges to achieving the effective and appropriate response are mainly directed to the coastal states of the Gulf of Guinea. The policies are clear and precise; the legal and operational issues are still not up to those policies, but the international community has, especially the EU, its efforts in place to assess and improve the regional capacities, knowledge and means in order to attack effectively the threat of piracy.

The three key actions to maintain secure waters in the Gulf of Guinea are surveillance, response and enforcement, every one of it developed at different pace in the countries of the region; hence, international cooperation is vital to reaching the regional and national objectives against piracy.

Versión PDF

Año CXXXX, Volumen 143, Número 1009

Noviembre - Diciembre 2025

Inicie sesión con su cuenta de suscriptor para comentar.-