By RODRIGO PELAYO GONZÁLEZ

The Chilean National Doctrine for Joint Planning, developed from foreign doctrines, considers the process of operational design, integrated to the operational planning, but in a way in which the moment of its application is not clearly defined and, in the long run, generates a duplicity of effort and confuses planners. The differences between operational and tactical planning, forces to rethink which is the best methodology to determine the problem and find the solution. In this respect, there is a lot to be discussed.

Naval operations planning during the twentieth century, at least from a didactic perspective, consisted of the reception of a directive from the superior level, identifying in it what that superior had to achieve (its purpose), determining the essential tasks that the recipient of the directive had to comply to contribute to that purpose, and join both -task and purpose- in a structure that summarized in a few lines the commander's problem: the mission.

At the beginning of this century, planning theorists realized that the mission in itself was insufficient to guide the courses of action that went beyond the fulfillment of tasks. Neither did they encompassed conditions for completion, or desired end state, that would ensure the success of the campaign, not only at the operational level, but also contributing to the success at the strategic and political levels.

The connection between the objectives of the different planning levels became fundamental, to the point of making it unthinkable that actions executed at the tactical level were planned with no other purpose than to contribute to the achievement of the strategic objectives. The operational level was born. This level, located between strategy and tactics, acts as an integrator, coordinator, and synchronizer of what the forces must achieve at the tactical level, structured in the form of operations and campaigns, and the fulfillment of the strategic objective.

The term "objectives," understood as goals to be achieved, began to appear more than "tasks" and "purposes”. The operational environment multiplied its complexity and dimensions, incorporating a more in-depth analysis of military, political, social, economic, cultural, and informational aspects, among others. Concepts such as center of gravity, decisive conditions and lines of operations appeared. The old and seemingly simple Operations Planning Process (OPP) was never the same.

This essay intends to postulate that, at the operational level, the planning process elaborated using the Operational Design (OD) methodology, eliminates the need to elaborate a guiding mission from the planning. Moreover, the arguments will show that OD, as a methodology aimed at framing the problem and elaborating a conceptual solution to that problem, replaces the whole orientation or analysis stage of the OPP mission and even part of the development stage of the concept or courses of action (COA).

Considering the aforementioned, the meanings of art, design, and operational approach will be reviewed, according to how they are understood by the national joint doctrine and how these concepts differ from doctrines of armed forces with more experience in the battlefields; Further on, OD will be explained as a methodology for solving military problems at the operational level; Later, the steps of the OD will be correlated to the steps of the OPP, indicating the duplicity of processes that implies to use both processes simultaneously. Finally concluding that OD is better applicable at the operational level and of external form to the OPP, than in all the levels of planning and of integrated or simultaneous form, thereby eliminating the need to elaborate a mission.

In the Chilean MoD publication “Doctrine for planning joint operations”, the introduction of operational art is defined as a "process that translates strategy into action" (Chile, 2014). This introduction is the first obstacle for planners to help understand the true dimension of what it covers.

A more comprehensive definition is covered in the MoD publication “Doctrine for Joint Operations” which defines it as; “the cognitive approach of commanders and advisors -with the support of their skills, knowledge, experience, creativity, and judgment, to develop strategies, campaigns and operations, and organize and employ military forces, integrating goals, methods, and means (MDN, undated). The concepts of approach and process are totally different things.

This planning doctrine refers to Operational Design as;

“…the description that a commander makes of the general provisions to be taken by his forces to achieve the desired military end state. It is the commander´s visualization of how the operation should transform the current conditions into the desired end state; the way the commander wants the operational environment to look like at the end of the operations”. (MDN, 2014).

A careful reading allows one to realize that this definition is not referring to the OD methodology, but rather to its result, the operational approach. This is a second relevant error, since it contributes to many planners referring indistinctly to design and approach, without understanding that the latter is the product of the former.

In this regard, the US joint planning doctrine correctly defines OD as a methodology designed to understand the situation and the problem; “operational design supports operational art with a general methodology using elements of operational design for understanding the situation and the problem” (USA, 2011). This is consistent with the current implementation in our OPP, where we incorporate the design methodology in the orientation phase (mission analysis) as an additional tool for the commander to achieve the deepest possible understanding of the problem he will face.

But what the Chilean planning doctrine omits when defining Operational Design (OD), is that delimiting the problem is not the final product of this methodology, but a previous step to the elaboration of a conceptual solution of this problem, in the form of an operational approach that gathers and orders, in time, space, and purpose, all the conclusions obtained in the previous steps.

Relying on conventional elements of art and design, within which the main ones are; the Desired End State (DES), the strategic and operational objectives, the Center of Gravity (COG), the Decisive Conditions (DC) and the Lines of Operation (LOO) from which DC occur. The United States doctrine clarifies this as; “the methodology helps the JFC and staff to understand conceptually the broad solutions for attaining mission accomplishment and to reduce the uncertainty of a complex operational environment” (USA JP 5-0, 2011).

As suggested at the beginning of this essay, the increasing complexity of military problems faced by an operational commander, made it necessary to seek methodological tools other than OPP.

In the related literature, it is possible to find various classifications for the types of military problems; however, in Western military doctrines, two general types are employed: well-structured and ill-structured (Hartig, 2005).

A well-structured problem is one in which the starting point, or initial situation are clearly defined and delimited, its goal is clear, and the possible solutions are verifiable and measurable. The solution to these types of problems was what last century´s commanders had to plan, when operational level was not yet the lead character in major operations or campaigns. Many writings associate these types of problems to tactical missions, with well-defined tasks and purposes and a wide range of possible courses of action for its compliance. But keep in mind: a well-structured problem does not imply that it is not extremely complex to solve, only that is associated with closed systems that can be solved by linear and analytic processes.

On the contrary, ill-structured problems are associated with open systems in which rational processes like OPP are insufficient. These have diffused and unclear goals, contradictory and incomplete requirements and information, whose partial solutions can generate new problems and for which possible solutions or courses of action (COA) are far from being numerous or perfect. These types of problems, with more complex and varied elements than just military, puts commanders and their planning staff in a difficult situation to understand its purposes and forms. Nowadays these problems are associated with operational level planning and gave birth to OD as a solution methodology.

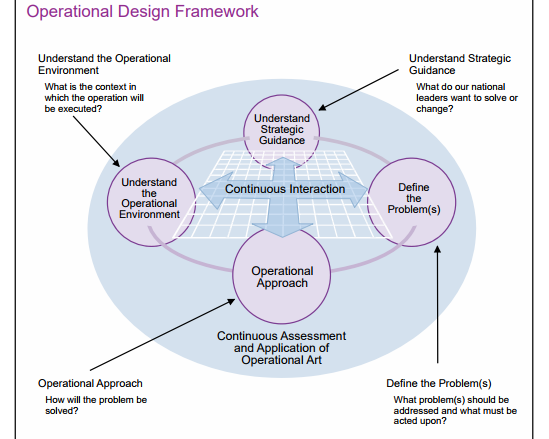

The joint doctrine of the armed forces, which are at the forefront in terms of planning process, mainly because of their experience in world conflicts, distinguish OD as a methodology that follows four steps that can be summarized as; 1) Understand the superior (in terms of desired end state, objectives, limitations, and other guiding aspects); 2) Understand how the operational environment is composed and how it impacts the achievement of the objectives (conclusions regarding the operational factors space, time, force, and information present in all possible dimensions of a theater of operations); 3) Determine the problem (those aspects of the adversary and the operational environment that prevent or make it difficult to move from the current condition to the desired end state, and 4) Develop an operational approach that visualizes, in graphic and narrative terms, the commander's conceptual solution. (USA JP 5-0, 2011)

Fig. 1: Operational Design Framework (2017 2014, p. IV-7)

At the operational level, where OD is best applied, the strategic level sets the campaign’s strategic objective and, immediately, this objective generates the creation of a theater of operations and the commander in charge. The operational commander then analyses and concludes whether a large operation is sufficient to achieve this strategic objective or a whole campaign will have to be designed. A campaign, defined as more than one major operation that, in a sequential or parallel, coordinated, synchronized, and integrated way, will reach the strategic objective. This strategic objective, which guides all operations of the campaign, is nothing more than the purpose of the commander; the “why” of the whole campaign. The major operations, on the other hand, are going to generate the operational or intermediate objectives that lead to the strategic or ultimate objective, which become the essential tasks to achieve the purpose, making a simile with the orientation stage of the OPP. With the strategic and operational objectives, we already have the “what” and the “for what”; we no longer need to develop a mission analysis stage.

Lines of Operation (LOO) and Decisive Conditions (DC) envisioned after a rigorous systemic analysis of factors; force, space, time, and information, becomes a "how". In broad terms, the commander thinks he must achieve the strategic objective and, therefore, they become limitations to creativity of detailed planning that formerly use to be emphasized in the way of thinking in many courses of action.

The LOO and CD, visualized after a rigorous systemic analysis of force, space, time and information factors, become a "how", in broad terms, the commander thinks he must achieve the strategic objective and, therefore, limiting the creativity of the detailed planning that used to be emphasized in the way of thinking in many courses of action. Operational approach can be understood as the framework of the definitive course of action, in the absence of detailing the effects that will comply with the decisive conditions, specific moment of analysis of alternatives. The above is consistent with what the department of Joint Military Operations of the Naval War College states;

“the design approach, therefore, does not recognize the need (or desire) for multiple courses of action. Nor does it recognize the formal process of analysis and comparison because those activities are accomplished through the discussion and framing of the problem” (NWC, 2019)

The U.S. Joint Planning Doctrine acknowledges that the OD and PPO are complementary, not integrated, elements for solving complex military problems; “operational design (OD) and joint operational planning process (JOPP) are complementary elements of the overall planning process” (USA, 2011). The US Navy´s doctrine of naval operations planning views OPP as an optional methodology, applied before or in conjunction with mission analysis:

“the NPP views design as an optional methodology that may be used in concert with operational art prior to and in conjunction with mission analysis in order to assist the commander and staff when faced with an unfamiliar or complex and ill-structured situation” (Navy, 2013).

The US Naval War College, in its academic syllabus at the operational level, suggests that, in the face of ill-structured problems, OD applies better than OPP, implying the independence of both processes: “for such complex adaptive systems and/or ill-structured problems, the design approach is preferred” (NWC, 2019).

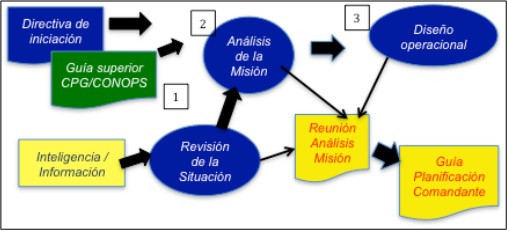

The OPP as a military problem-solving methodology is independent of the OD. It begins with the orientation stage, the purpose of which is; "to determine what must be done to satisfy the indications disposed by the superior" (MDN, 2014); that is, the “what” and the “why” (purpose), and has as its main product, the commander's mission. In the description of the steps of this stage, elements of the OD are interspersed without mentioning how they are obtained or where they come from, along with sub-processes that, expressed in other terms, do not differ in any way from the steps of the OD. Understanding the superior is now called "review of the directives and orientations of the superior" plus "task analysis"; understanding the operational environment changes to "review of the situation and analysis of key factors"; and identify the problem, along with developing the operational approach, are summarized in the development of a mission to guide the subsequent development of courses of action (COA).

Why then, even though the doctrines we use as references to elaborate our own recognize these two processes as alternatives, in the Chilean armed forces we have so much difficulty in separating them? In the author's opinion, the initial incorporation of the concepts of operational art, design, and approach to the educational and practical processes could have been rushed and without the full understanding of what they meant and how they paired with OPP, added to the fact that our doctrine updates have been kept at an unsatisfactory level.

The inconsistency is such that DNC 5-0 incorporates OD as a subsequent step to having established the mission, which is completely illogical because if you already have the “what to do” and “for what” purpose, after a thoroughly analysis of the operational environment, then, repeating the processes, makes no sense. Apart from that, just reviewing publications and graphic operational approaches from various foreign (including domestic) military organizations is sufficient to confirm that, within the elements represented, the mission is not one of them, since the desired end state and the objectives are more than enough to disclose the “what” and the “why.”

Fig. 2: Fig. 2 Operational design timing according to joint national doctrine (source DNC 5-0)

Our academic processes show that by planning simultaneously with OD and OPP, it often happens that the operational approach is then inconsistent with the course of action developed, since planners carry out OPP sub-processes that are meant to solve a mission, not an approach. Without going any further, the validity test refers to; "if executed in the described manner and the phases are fulfilled in the order and time intended, the COA will succeed in fulfilling the mission?" (MDN, 2014), whereas leading international doctrines validate the operational approach as "can accomplish the mission within the commander's guidance”. (USA, 2011)

It is valid then to ask us; If for the operational level, OD products are a clear determination of the problem and a conceptual solution to that problem; What is the need for the orientation stage (mission analysis) of the OPP?; If the operational approach results in a conceptual solution, with LOO and DC, ordered in time, space, and purpose, constitute the best possible vision of a commander on how to take an enemy´s COG out of the equation and meet the objectives and desired end state delivered by his superior; Why not move directly from the operational approach to the development of courses of action?

Adopting planning processes from foreign military organizations has its risks. One of them is mistakes in translation and interpretation. Another is incorporating these processes in full, as our doctrine, without evaluating what aspects are or are not applicable to our reality. But perhaps the greatest risk is maintaining the inertia without reviewing and improving our processes, meanwhile real-life experiences are warning us that these processes are not being correctly understood.

Both OPP and OD are methodological tools for solving military problems in the 21st century; however, the operational environment that an operational commander faces is far more complex and much less structured than that confronted by a tactical commander. Therefore, it requires a methodology that deepens his analysis with an approach beyond the rational, focused on the commander and using operational art as an ally. Although both processes can be applied at all levels, OD is more suitable for the operational level, and OPP for the tactical.

Our joint planning doctrine must be reviewed.

If the operational commander decides to plan exclusively with OD as a tool, as this essay suggests, then the timeframe to understand the problem and develop the operational approach must be sufficiently broad so that the analysis carried out can adequately enclose the problem. At the same time, devise a conceptual solution for the planners to dress it up with the effects that will detail the concept of operations, but maintaining the commander's lines of operations (LOO) and decisive conditions (DC). We must consider changing the mentality to work, from many to only one, or at most, two courses of action, and condition its validity to the operational approach. With this vision, the analysis of a mission is meaningless.

If the operational commander decides to plan to use indistinctively OD and OPP, it becomes necessary to reach a consensus as to properly integrate each of the steps. Both the OD and OPP contain steps with different names, but that seek the same conclusions. To keep the joint planning doctrine as it is, means duplication of effort and confusion. If this vision is adopted, the suggestion is that the Operational Design be considered external and prior to initiating the Operation Planning Process, on the condition that the operational commander deems it necessary.

For tactical level planning, OPP can be maintained unaltered, were tasks and guidance from the operational commander are sufficient, and a mission that guides through a superior purpose, is still suitable. At the operational level, things are different

&&&&&&&&&&&&

Versión PDF

Año CXXXX, Volumen 143, Número 1009

Noviembre - Diciembre 2025

Inicie sesión con su cuenta de suscriptor para comentar.-